What is end-to-end encryption?

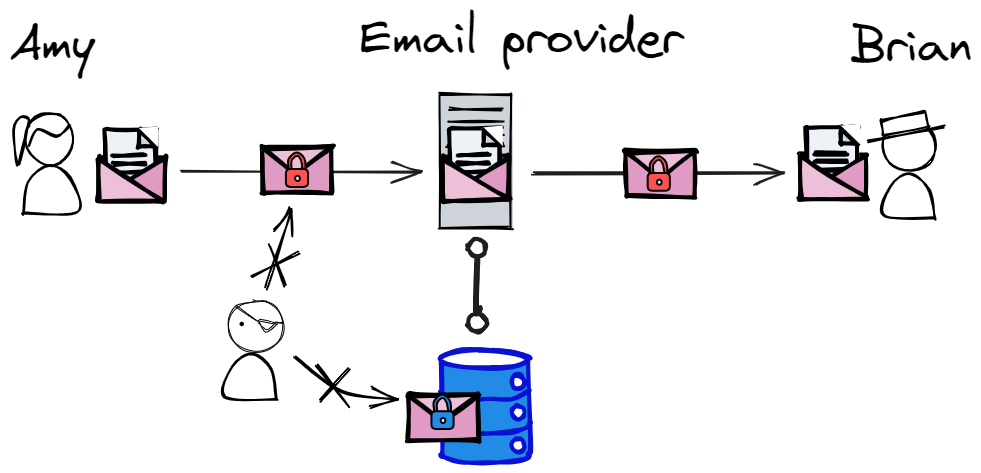

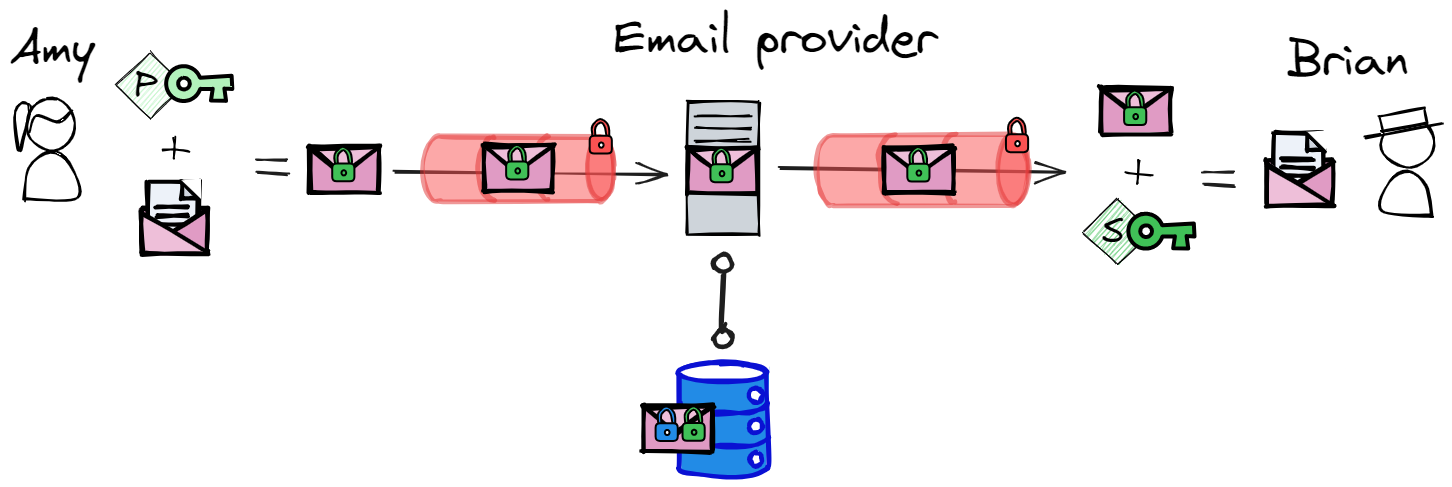

If Amy wants to send an email to Brian the email will transit by the email provider you are using. This can for instance be Gmail or Outlook. The email provider is responsible for relaying the email to its destination.

Broadly speaking there are 2 ways your email could be accessed by unwanted third-parties:

- When the email is in transit from your laptop to the email provider. However, HTTPS ensures a secure communication between your laptop and the email provider’s servers. It guaranties that nobody can impersonate the email provider and provides a secure communication channel between yourself and the servers.

- When the email is stored on the provider’s servers (at rest). The provider will store your emails on it’s server. This allows you to see the email on your mobile after sending it from your laptop. To prevent unwanted third-parties from accessing your emails, the provider will encrypt the email when it is stored.

Notice how the email is sometimes in plaintext format (

)

and sometimes in encrypted format (

)

and sometimes in encrypted format (

).

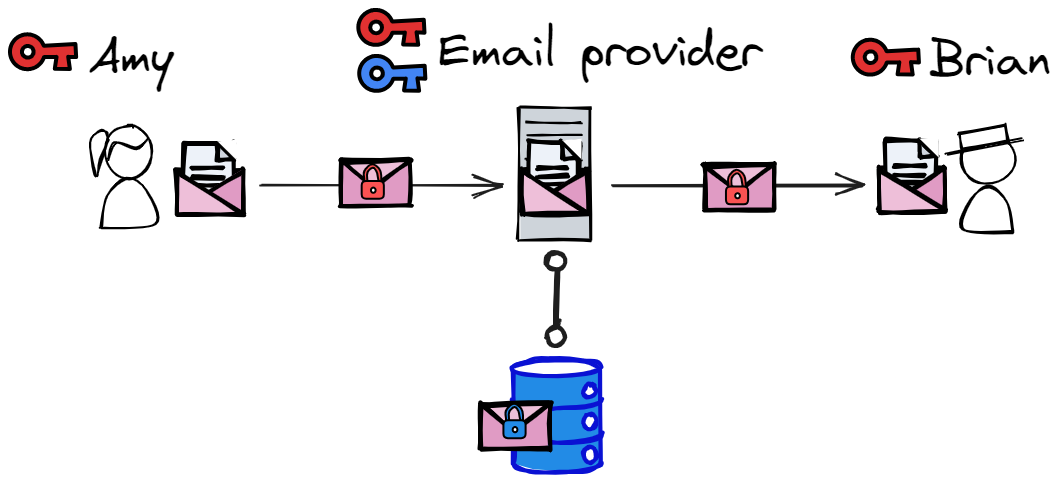

If your email is encrypted it means that it has been transformed

into a scrambled format which is unreadable. In order to recover the original information

you need a key which can decrypt the data. The next illustration highlights who has access

to the keys required for encrypting and decrypting the information.

).

If your email is encrypted it means that it has been transformed

into a scrambled format which is unreadable. In order to recover the original information

you need a key which can decrypt the data. The next illustration highlights who has access

to the keys required for encrypting and decrypting the information.

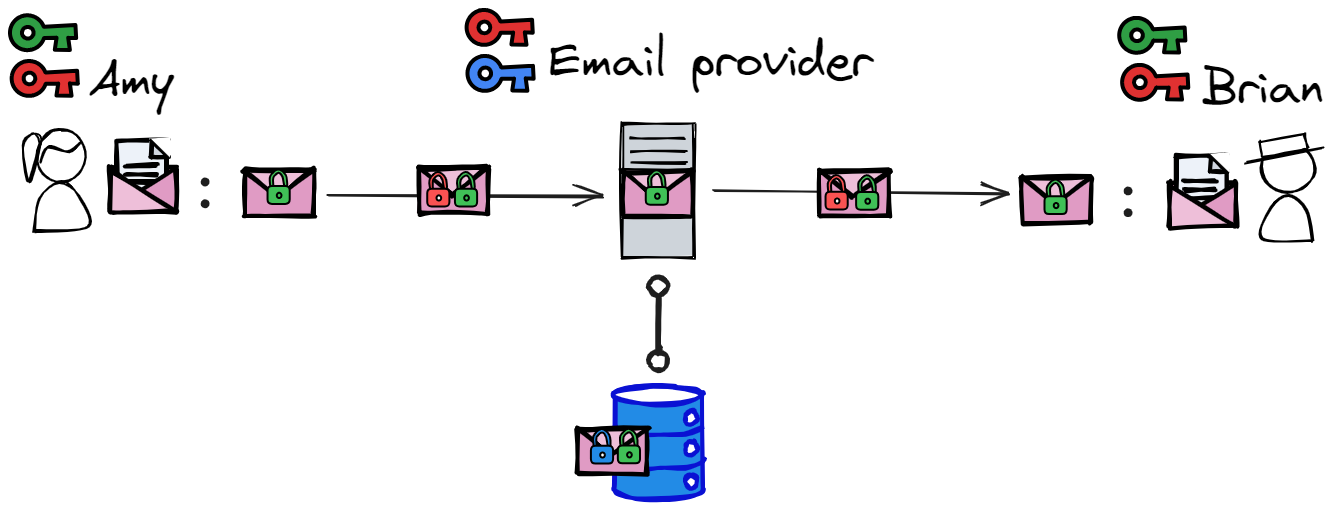

Encryption is a useful tool for preventing unwanted parties from accessing data.

If we want to exclude the email provider from accessing the data we can encrypt the email using a key only

Brian and Amy have access to (

).

).

Such a communication channel is called end-to-end encrypted because it guarantees that only the 2 ends of the communication channel (Amy and Brian) have access to the decrypted content.

Amy and Brian are both using the same key for encryption and decryption. This is known as symmetric encryption. The tricky part with symmetric encryption is that the key needs to be shared between Amy and Brian without anyone else getting their hands on it.

Implementing end-to-end encryption

This concept of ensuring privacy between the 2 ends of the communication was implemented in 1991 by Phil Zimmerman who wrote a program called PGP which stands for Pretty Good Privacy. You can use PGP to encrypt your email message before sending it to it’s destination and the recipient also uses PGP to recover the message once he receives the email.

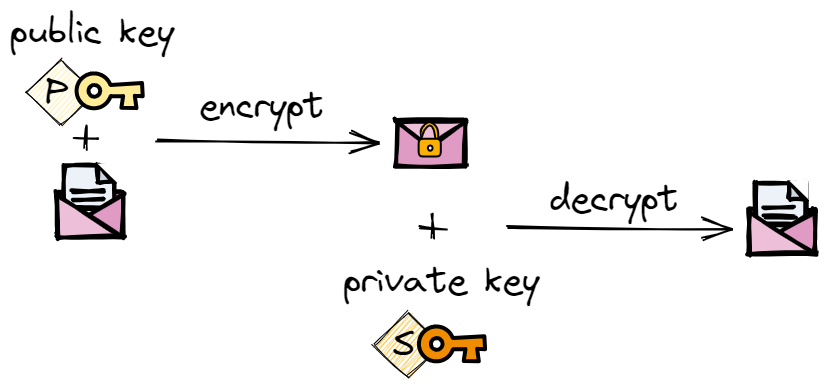

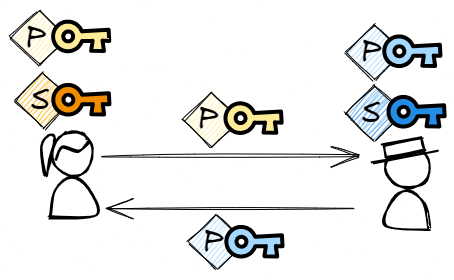

While diving into the details of PGP goes beyond the scope of this post, one important concept used by PGP is the concept of public key cryptography. With public key cryptography you generate 2 keys: the public key which can only be used to encrypt data and the private key (or secret key) used to decrypt the data encrypted by the public key.

In this scenario, only the public key needs to be shared between parties that want to communicate. Amy will share her public key with Brian and Brian will share his public key with Amy. Furthermore, the public key can only be used for encryption so even if it is intercepted by someone else this does not represent a risk because they will not be able to decrypt any message.

Now if Amy wants to send a message to Brian she can encrypt the message using Brian’s public key. Only Brian can decrypt the message because only he has access to the associated private key. Likewise, if Brian want’s to send a response message to Amy he can use Amy’s public key to encrypt the message.

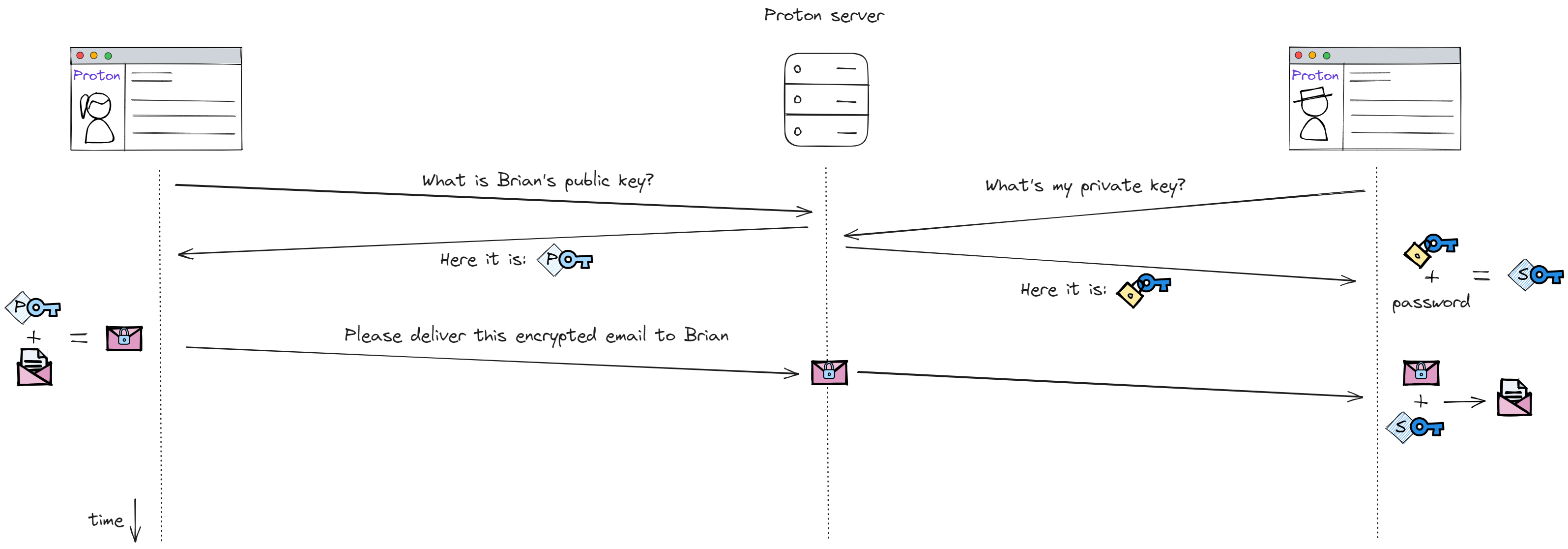

PGP depends on this key exchange to guaranty a secure communication between Amy and Brian. The following illustration shows a simplified view of how email communication works when using PGP.

As a software, PGP never gained widespread adoption. For a start it is very technical to use so difficult for those who are not tech-savvy. The security of PGP also depends on how well you can keep your private key secure which even for tech-savvy people can be too much to manage.

The team behind Proton Mail realized that to make encrypted email more widespread, the user experience should be closer to that of other providers such as Gmail or Outlook. The user should only have to login to his account, write his email and send it to the recipient without having to worry about encryption keys. While PGP provides a good cryptographic foundation for security, it’s main pain points had to be solved.

Proton Mail’s solution

Here are the 3 requirements that ProtonMail had to reconcile:

- PGP should be used to guarantee E2E encryption of email content.

- End users should not be required to manage their private keys or be in any way involved in the encryption process.

- It should be impossible for Proton Mail to access the email content (i.e. Proton Mail should never have access to the user’s private key)

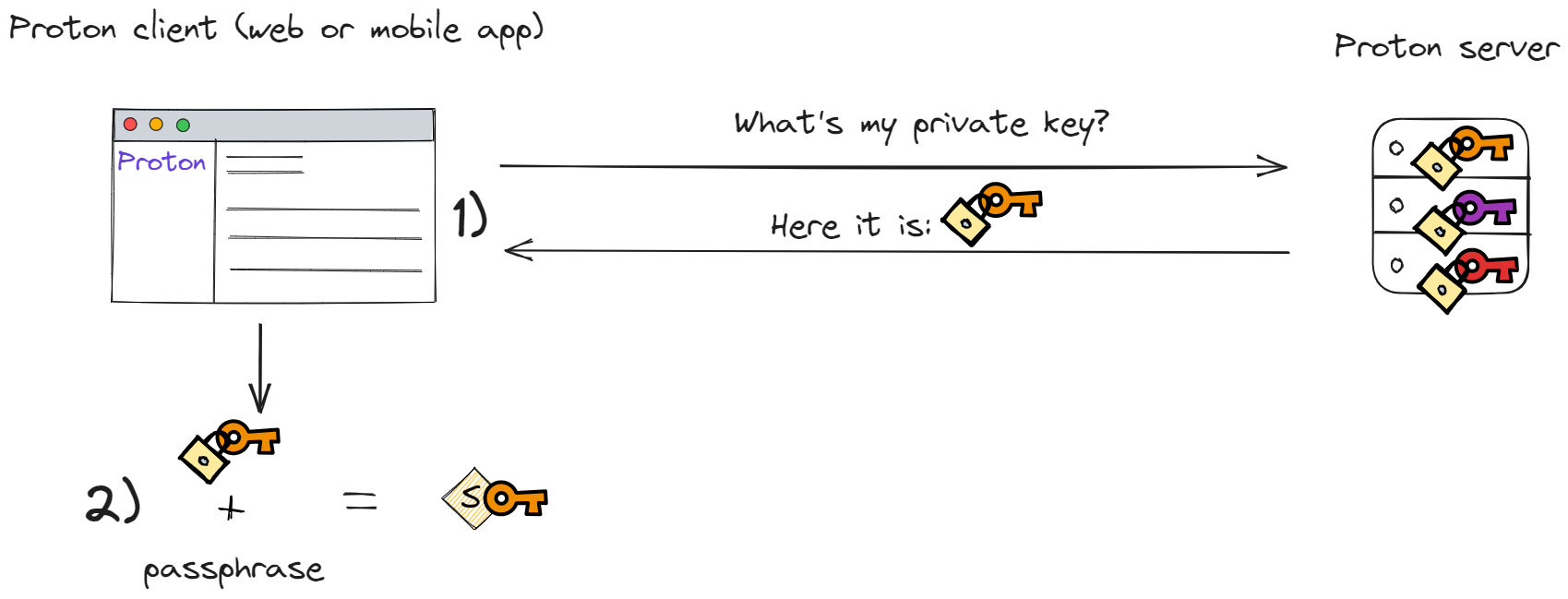

To solve 2. Proton needs to store your private key on its servers. When you access your emails either

from your desktop or mobile the client app will ask Proton’s server for your private key which will then be

sent over to you. To make sure that this approach does not conflict with 3., Proton only stores on its

servers a key which is locked with a passphrase (

).

A passphrase is to a key what a password is to

your account. The locked key is sent to the client where it is unlocked and then used to decrypt your

emails.

).

A passphrase is to a key what a password is to

your account. The locked key is sent to the client where it is unlocked and then used to decrypt your

emails.

The last question then is what is the passphrase used to lock your private key? Proton cannot keep this passphrase on it’s servers as that would defeat the purpose of locking the key in the first place. This means the passphrase should be accessible from any device when you connect to your Proton account but never stored by Proton. The only piece of information that fits this requirement is your password. Every time you connect to your Proton account you use your password to login. This password is then used by Proton’s web or mobile apps to unlock the private key sent to you by Proton servers.

If we combine this with what we know about secure email sending using PGP we get the following picture which is in a nutshell how ProtonMail works.

One key to rule them all

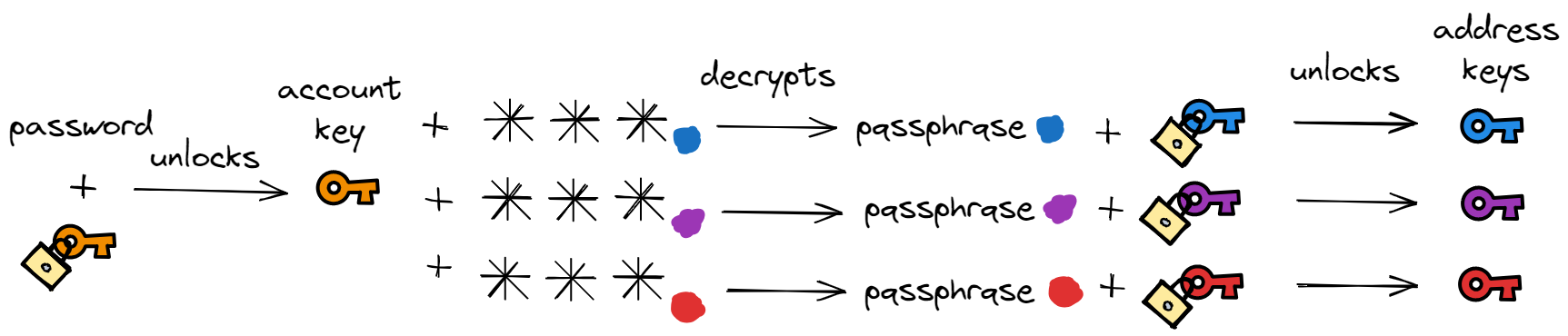

If you go to Setting → Encryption and Keys when logged in to your Proton account you will find that you actually have more than one private key. There is the “Email encryption key” (also referred to as the address key) and the “Account key” (also referred to as the user key) each having their own responsibility.

→ The account key is used to encrypt account wide information such as your contact list and is also used to recover your account in case you forget your password.

→ Address keys are used to encrypt and decrypt the content of emails being sent. For each email address you have there is one address key.

Your password is only used to unlock your account key. Each address key is locked by a passphrase which is randomly generated. Each passphrase is itself encrypted using your account key.

With this architecture we have access to multiple private keys all locked with different passphrases but there is only one piece of information that we need to remember which is our password.

The implications of this architecture is that your password isn’t just used for accessing your account but is also the foundation of how your email contents is encrypted. This means that if you lose your password you might be able to regain access to your account by means of recovery but your emails will no longer be readable because the keys used to encrypt their content can no longer be unlocked.

You can learn more about account recovery by reading the official documentation here.

Wrap up

By building on top of a proven technology and by using strong cryptography concepts Proton has managed to make end-to-end encryption available to a broad public. While the experience provided by Proton has abstracted away the underling encryption concepts some basic understanding of the primitives being used can help to better harness the privacy tools out there and be less reliant on simply “trusting” the service.

Proton decided to build on top of PGP but it is not the only way to ensure privacy of communications. For example Signal developed it’s own Protocol called the signal protocol and which is also in use by Whatsapp to support end-to-end encryption.